Bundles Interpolation

Stolen Messages

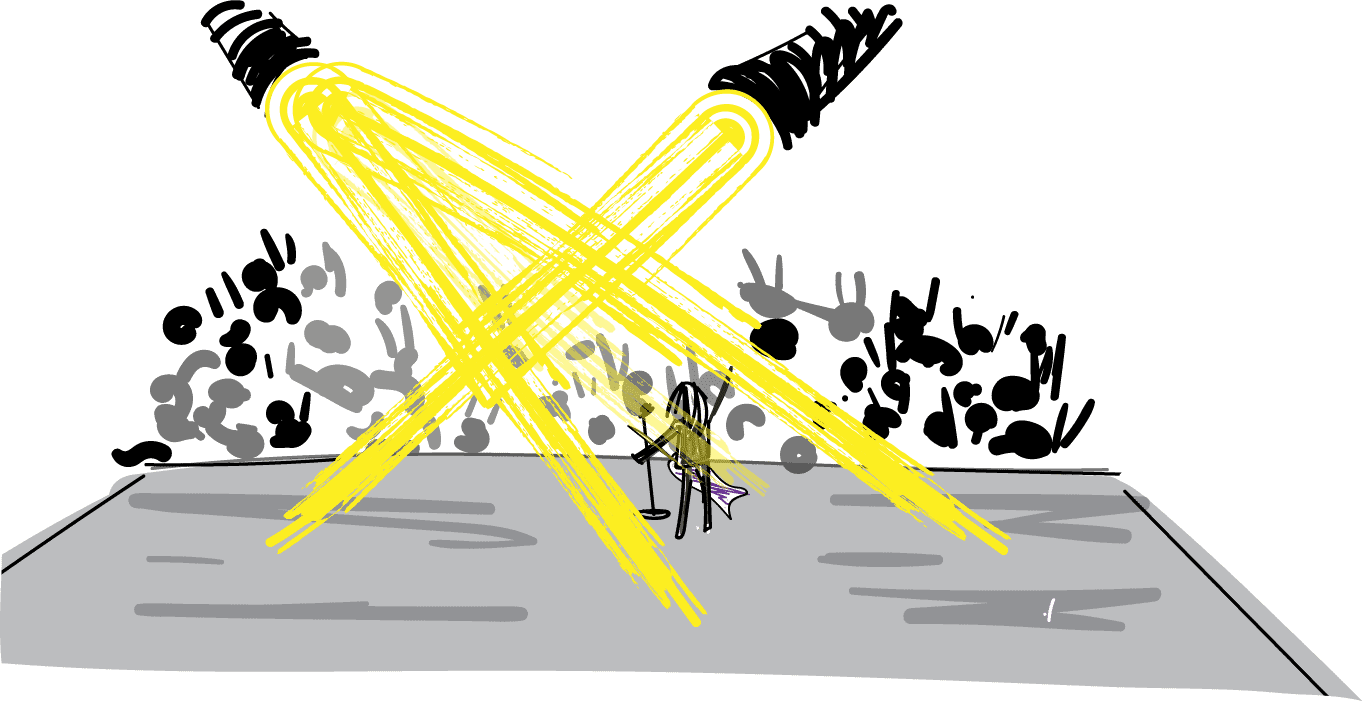

Alice is a rising celebrity who receives mail from her fans. They used to send mail directly to her.

new alice, stdout(`rho:io:stdout`) in {

// Alice reads fan mail

for (mail <- alice) {

stdout!("Alice received a fanmail")

}

|

// Bob sends fan mail

alice!("Dear Alice, you're #TheBest")

}But as she became more popular, her jealous competitor Eve began stealing her mail. (Imagine that Eve can run code inside the first set of curly braces.)

Exercise

Write the code for a competitor to steal the mail

The problem is that the competitors can listen on the same channel Alice can. So what she really needs is for her fans to have a "write-only bundle"

new alice, bob, eve, stdout(`rho:io:stdout`) in {

// Alice gets a lot of fan mail, so she

// creates a new write only bundle and publishes it.

new aliceFanMail in {

// Alice gives fanmail channel publicly

alice!!(bundle+ {*aliceFanMail})

|

// Alice also reads fan mail

for (mail <= aliceFanMail) {

stdout!("Alice received a fanmail")

}

}

|

// When Bob wants to send fanmail he asks for the channel

// and then sends

for (aliceFanMail <- alice) {

aliceFanMail!("Dear Alice, you're #TheBest")

}

|

// Eve tries to intercept a message, but cannot

// because Alice's fanmail channel is write-only

for (aliceFanMail <- alice) {

for (@stolenMail <= aliceFanMail) {

stdout!(["Eve stole a message: ", stolenMail])

}

}

}The bundle+ {*aliceFanMail} is a channel just like aliceFanMail except it can only be sent on, not received.

Subscriptions

The bundle solution above does prevent Eve from stealing mail, which is good. But in the blockchain context it also has the unfortunate side effect that Alice has to pay to send her fanmail address. Blockchain fees work a little like postage.

Exercise

Alice can save postage by making fans request the fanmail address from her. Then they will have to pay the transaction costs. A bit like sending a return envelope with a stamp already on it.

Complete Alice's code so that she can get Bob the address he needs.

Here's the answer:

new alice, bob, eve, stdout(`rho:io:stdout`) in {

// Alice get a lot of fan mail, so she

// creates a new write only bundle and publishes it.

new aliceFanMail in {

// Alice returns fanmail channel to any fan that asks

for (return <= alice) {

return!(bundle+ {*aliceFanMail})

}

|

// Alice also reads fan mail

for (mail <- aliceFanMail) {

stdout!("Alice received a fanmail")

}

}

|

// When Bob wants to send fanmail he asks for the channel

// and then sends

new return in {

alice!(*return) |

for (aliceFanMail <- return) {

aliceFanMail!("Dear Alice, you're #TheBest")

}

}

|

// Eve tries to intercept a message, but cannot

// because Alice's channel is write-only

new return in {

alice!(*return) |

for (aliceFanMail <- return) {

for (@stolenMail <= aliceFanMail) {

stdout!(["Eve stole a message: ", stolenMail])

}

}

}

}Astute readers will notice that Eve can now just intercept messages asking for the fanmail address. Good observation. As a bonus exercise, you could write Eve's new code. (hint: it's the same as the old code). The solution to this problem involves public key cryptography and the registry. We'll learn about that later on.

Exercise

Our pizza shop back in lesson 2 had a similar problem to Alice. Rework that code so they can easily take on new customers.

Jackpot

I used to play a game called jackpot as a kid. One player would throw the ball and yell a number. The other players would all try to catch the ball and whoever caught it would receive that number of points.

Playing jackpot is just the opposite of sending fanmail. Before there were many fans all sending to one celebrity. Now there is one thrower, sending to one of many recipients

new throw, stdout(`rho:io:stdout`) in {

// Throw the ball worth five points

throw!(5)

|

// Throw the ball several more times

throw!(4) |

throw!(2) |

throw!(6) |

// Bill and Paige both try to catch

for (points <= throw){

stdout!("Bill caught it")

}

|

for (points <= throw){

stdout!("Paige caught it")

}

}Who will catch the ball in the jackpot code?

- Bill because his catch code is first.

- Bill because his catch code is closest to the throw code.

- Paige because her catch code is last.

- We don't know; it is nondeterminate.

Exercise

Exercise: Use stdoutAck to display how many points each person actually gets when they catch the ball.

How is this game in rholang different than the real game where one ball is thrown repeatedly?

- It is a very accurate simulation

- In rholang all balls are thrown concurrently and caught in any order

- In rholang the balls are caught in the reverse order from what they are thrown.

- In rholang Bill makes all his catches, then Paige makes all her catches.

Side Bar: String Operations

Most programming languages will allow you to join or "concatenate" two strings together, and rholang is no exception. We can stdout!("Hello " ++ "world"), but we can't concatenate a string with an int.

One solution is to use stdoutAck andsend acknowledgements. Another option is to print a list stdout!(["Bill caught it. Points earned: ", *points]). We'll go into more detail about both techniques in future lessons.

A final option is to use string interpolation. String interpolation allows you to put placeholders into your strings and replace them with actual values using a map.

new stdout(`rho:io:stdout`) in {

printStuff!({"noun": person, "adverb": sideways}) |

contract printStuff(map) = {

stdout!("The ${noun} jumped ${adverb}" %% *map)

}

}You can learn more about how the map that gets sets in lesson 12 on data structures.

Imposter throws

Notice that anyone can come along and mess up this game by throwing fake balls. This is just the opposite of Eve coming along and stealing Alice's fanmail.

What code would Eve have to par in to throw an imposter ball worth 100 points?

- for (imposter <- throw){imposter!(100)}

- throw!(100)

- @"throw"!("100")

We solve this problem by making sure that the public can only read from the throw channel, but not write to it.

new gameCh, stdout(`rho:io:stdout`) in {

new throw in {

//Give out read-only access

gameCh!!(bundle- {*throw})

|

// Now actually make all the throws

throw!(4) |

throw!(2) |

throw!(6)

}

|

// Bill and Paige join the game

for (throw <- gameCh){

for (points <= throw){

stdout!(["Bill caught it. Points: ", *points])

}

}

|

// Eve tries to throw a fake, but can't

for (throw <- gameCh){

throw!(100)

}

}Like before, this code requires the game host to pay for everyone who get's the bundle from him. It could be refactored so players have to subscribe to the game like we did with Alice and her fan mail.

Public Key Crypto

In some ways, read-only bundles duplicate the signing features of public-key cryptography. The jackpot catchers here are sure that the balls came from the thrower because only he can send on the throw channel, which is a lot like cryptographic signing.

In some ways write-only bundles duplicate the encryption features of public-key cryptography. Only Alice can receive messages sent on her fan mail channel. One very important difference is that the messages sent here are 100% visible from outside the blockchain! So while write-only bundles are an effective way to communicate unforgeable names, they are not a good way to plot a heist, or evade government surveillance. Be Careful!

More About Bundles

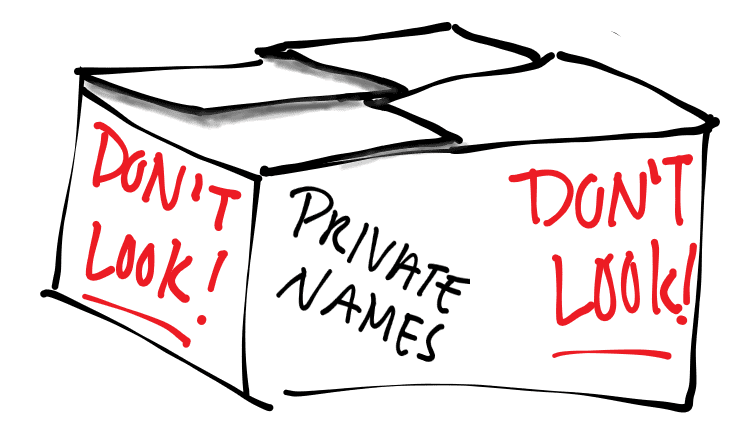

In addition to read- and write-only bundles, there are two other types that are also useful.

| Syntax | Can Read | Can Write |

|---|---|---|

bundle- {proc} | YES | NO |

bundle+ {proc} | NO | YES |

bundle0 {proc} | NO | NO |

bundle {proc} | YES | YES |

You may be wondering why a bundle on which you can neither send nor receive would ever be useful. Given what we've learned so far, that's a wonderful question. When we discuss pattern matching next unit, we'll see that bundles do more than restrict read- and write- capabilities. They also prevent taking compound names apart to look inside.