Unforgable Names

We've learned how to receive messages with for and contract. Both of these constructs "bind" variables. A variable is considered bound if has an actual value (a channel or a process) attached to it.

Bound and Free Variables

Consider this real-world example. My sister's name is Sarah. When I speak to my family members about "Sarah" they know who I am talking to because they also know my sister. So "Sarah" is a bound variable. It is bound to the person who is my sister. But if I walk up to a random person on the street and talk about "Sarah" they may understand the general point of the story, but they do not know who it is about. Because for them "Sarah" is not bound to any person. For the random stranger, "Sarah" is a "free variable."

Getting back to rholang, order is initially a free variable, but it gets bound to whatever message comes in on the coffeeShop channel.

for (order <= coffeeShop) {

stdout!("Coffee Order Received")

}The same is true when we use contracts.

contract coffeeShop(order) = {

stdout!("Coffee Order Received")

}State whether x is bound or free in each of the following code snippets.

for (x <- y){Nil}

- Bound

- Free

- Neither

for (y <- x){Nil}

- Bound

- Free

- Neither

new x in { x!(true) }

- Bound

- Free

- Neither

contract x(y) = { Nil }

- Bound

- Free

- Neither

contract y(x) = { Nil }

- Bound

- Free

- Neither

for (y <- x){Nil}

- Bound

- Free

- Neither

The new Operator

for and contract are perfect for binding variables inside of continuations. It turns out that the new operator also binds variables. What does it bind them to? Brand new channels that we can use to send messages on.

new pizzaShop, stdout(`rho:io:stdout`) in {

// Same contract as before

contract pizzaShop(order) = {

stdout!("Order Received.")

}

|

// Known customers can order because pizzaShop is bound here.

pizzaShop!("Extra bacon please")

|

pizzaShop!("Hawaiian Pizza to go")

}// But we can't order from here, because pizzaShop doesn't exist

What happens when you try to order a pizza from outside of the new restriction.

- The order works fine

- The order works but takes much longer

- Error about top-level free variables

- The code runs, but no order is received

We learned that all names quote processes. So what process does the pizzaShop name quote? Try printing the process to stdout to see

- It quotes "pizzaShop"

- It doesn't quote anything

- "Some Unforgeable hex code"

In rholang channels created with new don't give access to the underlying process that they quote. You can think of them as being "pure channels" if you like.

Private vs Unforgeable

new is known as the restriction operator because it restricts use of the bound names that it creates to within its curly braces or "lexical scope". Within the world of the rholang these new names really are only visible within the correct scope, but remember that human programmers can look in to that world from the outside. That is especially true when working in a blockchain context.

So while a competing pizza shops (from outside the curly braces) can not consume pizza orders intended for our shop, they can still read the orders with a block explorer. Occasionally programmers call new names "private", but a better term is "unforgeable", which explains the answer to the previous question.

Acknowledgement Channels

One common use of unforgeable names is "acknowledgement channels", usually called "ack" channels for short. Instead of confirming orders by printing to the screen and disturbing everyone, the pizza shop should really just let the customer know that the order has been placed.

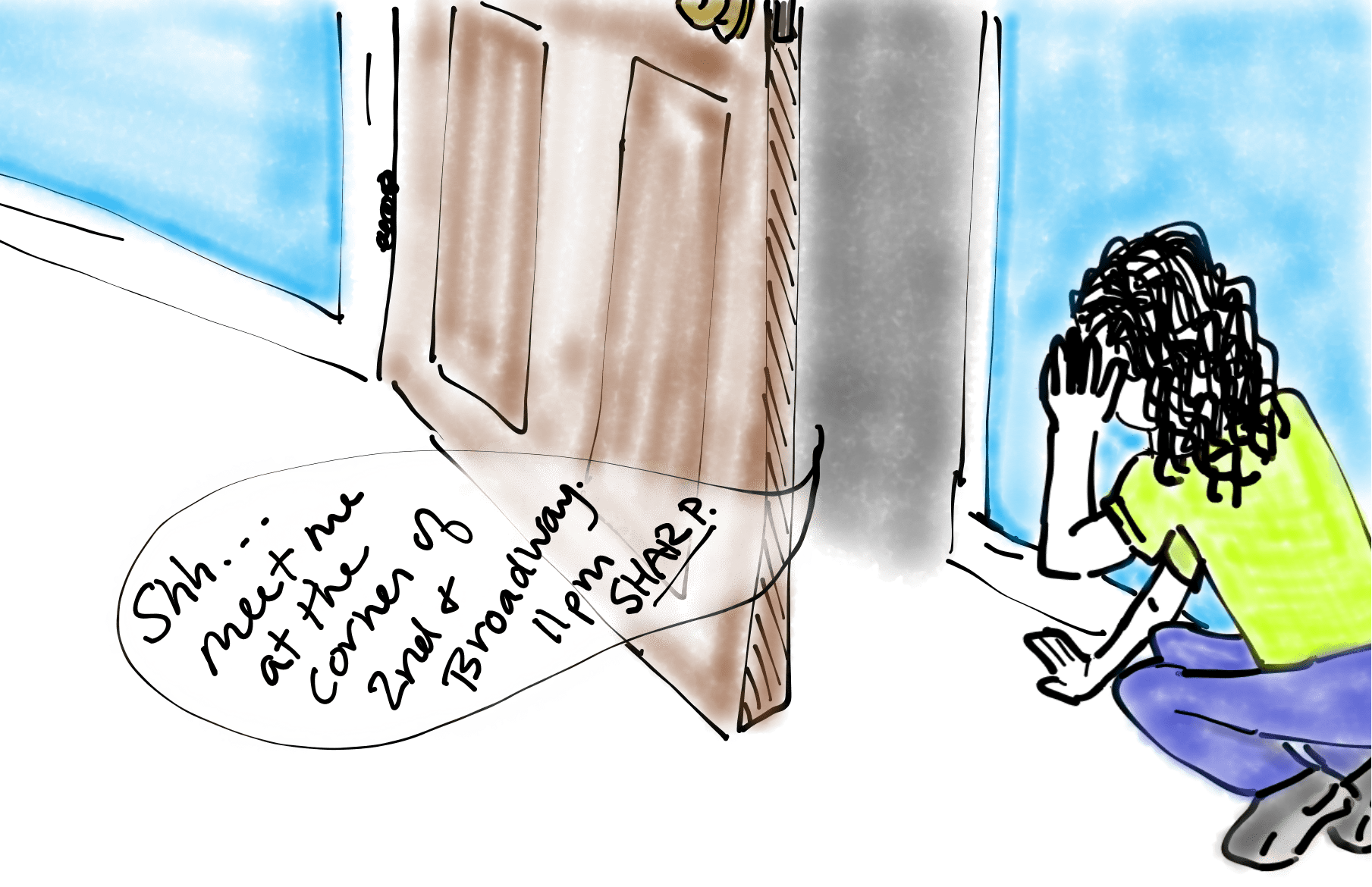

To do that the pizza shop needs to know how to contact the customer. So the customer should supply an acknowledgement channel to be called back on. Traditionally such a channel is named ack.

new alice, bob, pizzaShop in {

// Now we take an order and an ack channel

contract pizzaShop(order, ack) = {

// Instead of acknowledging via stdout, we use ack

ack!("Order Received.")

}

|

// Known customers can order because pizzaShop is bound here.

pizzaShop!("Extra bacon please", *alice)

|

pizzaShop!("Hawaiian Pizza to go", *bob)

}Why don't the acknowledgements in the previous example show up on the screen?

- There is a bug in the code

- The orders were not received correctly

- The confirmation was not sent to

stdout

Sending Names Gives Permission

We just saw how the customer can give the shop an ack channel to receive order confirmation. It turns out we can do even better. With our previous code, Bob could contact Alice on her ack channel. That means Bob could send a forged ack making Alice think the order was placed when really it wasn't. Really Alice and Bob should keep their unforgeable names under tight control. Because giving someone that name gives them the capability to contact you.

new pizzaShop in {

// Take orders and acknowledge them

contract pizzaShop(order, ack) = {

ack!("Order Received.")

}

|

// Order a pizza and send a private ack channel.

new alice in {

pizzaShop!("One medium veggie pizza", *alice)

}

}The solution is to create a new unforgeable name, and give it to the pizza shop so that only they can call you back. Even though the pizza shop is outside of the new alice, it can still send on the channel because Alice gave it the channel's name. This is a wonderful way to delegate privileges.

In this example we trust the shop to only send on the ack channel, but notice that it could also receive if it wanted to. We'll learn how to give out only some of those permissions in the next lesson on bundles.

Bob also wants to order a pizza and give a unforgeable ack channel. Where should he create his unforgeable channel?

- On his own line, after the alice code

- On the same line Alice did

- On the very first line of the program

stdoutAck and stderrAck

Now that you understand ack channels, you should know about two other ways to print to the screen. They are channels called stdoutAck and stderrAck. They work just like their cousins from lesson 1, but they take an ack channel.

new myAckChannel,

stdout(`rho:io:stdout`),

stdoutAck(`rho:io:stdoutAck`) in {

stdoutAck!("Print some words.", *myAckChannel)

|

for (acknowledgement <- myAckChannel) {

stdout!("Received an acknowledgement.")

}

}By the way, did you ever notice the handful of stuff that always starts in a fresh tuplespace? Four of those things are the built-in receives for the screen-printing channels. The others are for cryptography. We'll discuss them later.

Exercise

stdout!("1") | stdout!("2") | stdout!("3")

Notice that this program does not print the numbers in any particular order. The calls happen concurrently. Imagine we really need these lines to print in order. Modify the code to use ack channels and ensure that the numbers get printed in order.

Exercise

Predict how this program will run (what it outputs and how it reduces in the tuplespace). Then run it to test your prediction.

new myChan in {

myChan!("Hi There")

}

|

for (msg <- myChan) {stdout!(*msg)}If your prediction for the previous exercise was wrong, modify the program so it actually does what you predicted it would.

Quiz

Which name is bound in for(x <- y){Nil}

xyNil

Which name is bound in new x in {Nil}

xyNil

If pizzzaShop is a name, then what is @pizzaShop?

- A name

- A process

- Invalid syntax

Why did the pizzaAck code send *bob as an ack channel instead of bob?

- No reason; it's just a style choice.

- Because

bobis a channel, but we have to send processes. - That's special syntax for ack channels.